Many children find writing difficult. Almost all children can write a sentence, yet even as they approach year 3, many of the children I meet struggle with the anguish of putting pencil to paper. The problem often starts with a blank sheet of paper. That space is a scary place for many. But that isn’t the only problem — many who struggle to write also struggle to decode and spell accurately.

Peter Reynolds discusses this in his book, The Dot about Vashi and her lack of marks on paper, and Abby Hanlon puts the problems across beautifully in Ralph Tells a Story. I use both books to calm the nerves of my students so they don’t feel entirely alone — if it is in a story, you’re not alone. Others have and do feel like this, too. I always think great conversations can come from books.

A story can soften the blow of a hard conversation. The type that makes you twist

and turn inside before you come out the other end feeling better.

Reading and talking about problems is one thing, but we must combat sentence fatigue by taking it slowly, working step by step, and modelling the process with lots of repetition through playful practice.

It’s crucial that when we help children build sentences, it starts orally. My students always have something to say as we meet or something to show me. They will often interrupt sessions with amazing facts and tales of the weekend. But when the tricky bit about writing begins, they have nothing to say. Talk of the bunny, the trip to the beach and do you know, “I am growing wheat in my bathroom,” all float away.

As many have said, including Pie Corbett of Talk for Writing and Ros Wilson of Big Writing,

“If you can’t say it, you can’t write it.”

We have to help children develop the habit of saying their sentence first. Next, say each word as they write. Finally, read back their sentence.

The talk of the beach, bunny, and wheat often involves sentences that would take too long to get on paper. These children are great communicators. They have lots to say. We must hone these skills through games and instruction so they come out the other side able to write.

There isn’t as much research about writing as there is for reading. This is an area that requires more research. The studies out there show that writing places a heavy load on working memory.

We know that if we provide scaffolds for writing, we reduce the demands of the task.

Working memory can’t hold onto anything for too long and can only hold a few items before all is forgotten. So, in the early years, it might feel a little overwhelming, especially because there is so much to think about:

the need to hold the pencil correctly,

thoughts about what to write,

how to write, and don’t forget the punctuation,

my t-shirt is a little itchy, and Archie keeps talking to me across the table.

It is all too much! It is no surprise that children struggle.

Starting with word games that can build up to be sentence games helps our young writers learn writing conventions step by step. Learning to write sentences takes time and lots of repetition. Playing games is an effective way to develop writing, creativity and vocabulary.

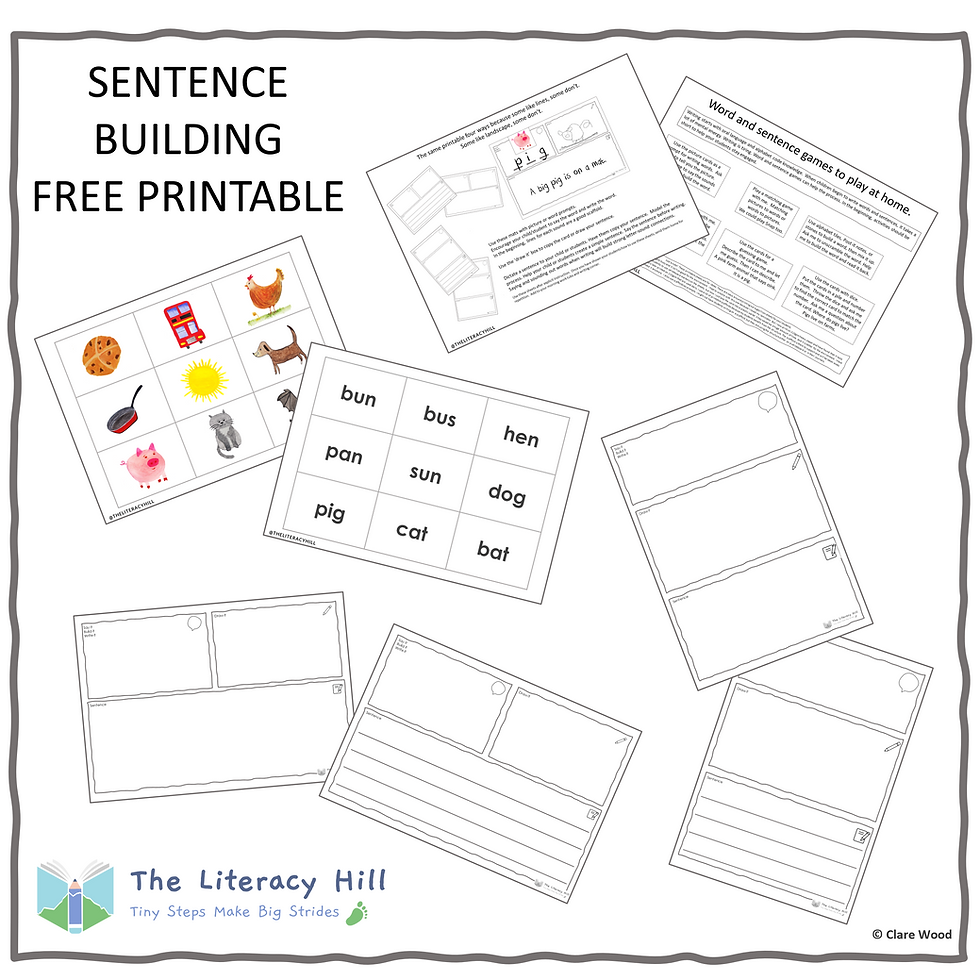

Use the picture cards as a prompt for writing words.

Ask me to tell you the picture. Prompt me to say the sounds as I write or build the word. Talk about the picture. Ask your child to describe the picture.

Build a word, then mix it up.

Use alphabet tiles, post-it notes or stones. Ask me to unscramble the word. Help me to build the word and read it back. We also used our word cards to read the words. Cut up the letters, mix up and unscramble. Add words to sentences.

We shouldn’t be asking our young writers to write at length — it should be quality over quantity.

Sentence games that move from word level to sentence level through to sentence combining can teach the conventions we need in phonics instruction sessions.

Sentence and word games help the writing process. Initially, activities should be short to help your students stay engaged.

Use a picture or a word as a prompt and encourage your child/student to describe the picture. We use these sentence mats to move from word level to sentence level.

Ask wh- questions to build the sentence.

Where is the pig? What is the pig doing? Later on, as your students become more confident, adding on to simple sentences with actions and describing words helps build longer sentences. Try using two or three prompts once your children get the hang of adding one word or picture prompt to a sentence.

Say the sentence. Repeat the sentence and count the words to know how many words should be on the paper.

Before writing, the oral construction of sentences must be a rigorous practice that becomes a positive habit. This is a great daily review activity. All students write a sentence because of a picture or word prompt. They can show their whiteboards to the teacher to quickly assess the writing. The teacher might also dictate a sentence. This helps to form good punctuation habits. Punctuation is tricky, but continued modelling and repetition will allow most children to punctuate a simple sentence by the end of their Foundation year. In the beginning, our young students need a solid foundation. Learning that a sentence starts with a capital letter, ends with a full stop and has to make sense on its own is enough new knowledge to handle. Once students have a firm grasp of writing sentences and can edit their own sentences, they can move on to writing paragraphs and more elaborate punctuation.

Explicit writing instruction is crucial from the beginning.

Check out the digraph activity books here.

We can’t expect students to write at length if we don’t teach them the mechanics of writing.

Students in the first year of school don't need to write at length. (That's not to say that some won't, some will want to write lots)

It is more important to teach how to write a sentence and put them on the right road to correct spelling by linking phonics instruction to writing instruction.

Use the picture cards from this resource to support sentence work.

We always start with a game of matching pairs.

Next, we did a quick write dictation of words to remind us of the target digraphs we have recently learned. Then, the students picked two words to add to a sentence. We all had a go at saying our sentence before writing.

To extend this activity, you could use a conjunction die to expand the sentences verbally. This primes later learning as students will become comfortable with sentence writing and how to expand correctly instead of run on sentences.

To find out more about this resource, go here.

A game can also lead to sentence instruction.

Games are a great way to sneak in lots of decoding practice, but they can also be a playful starter too.

My students love these track games and have no idea how much work they are actually doing! As we played, we added words to oral sentences. After playing, the students picked a word or two to add to a sentence. Everybody had a go at writing their sentence.

Learning how to write is tricky. There is so much going on — letter formation, spelling, what to write? Teaching the mechanics of writing playfully right from the start will build the skills and knowledge needed for later years.

Early writers know little code knowledge and can get tangled up in what they want to say. They can come up with brilliant sentences with too many tricky words. Dictation is a great activity to model how to write a sentence. This quick activity helps children feel successful because you have taken away the creating part. We often use our dictated sentences as an add on activity. This also doubles as a decoding activity because the children must read the sentence back to add extra detail.

Children have to build up their writing stamina. Most children won’t be able to write at length in the beginning. Writing should be a structured activity that builds on phonics instruction. Most will flounder if we ask young children to write without structure and instruction. I’m not saying that everything should be structured. There is a time and a place for emergent writing. But if we want our students to move swiftly, explicit writing instruction should start in the Foundation year.

Comments